Star's End

During the 1970s, the world of modern classical music managed to break in to the mainstream. In the US, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Terry Riley and other avant-garde composers started to be able to fill venues, and they came to have a heavy influence on the electronic music of the late 1980s and early 1990s, from The Orb and Orbital to Colourbox and Aphex Twin.

The UK also had a number of classical composers who were briefly mainstream in the 70s. They’ve never quite received the recognition of Glass or Reich, even in the UK, and I think that’s a shame.

One such composer was David Bedford. If you’ve ever noticed the complex orchestral arrangements on hits by Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Madness, China Crisis, Elvis Costello or Enya… well, those were composed by David Bedford, yet that’s probably news to you. It was news to me that the orchestral parts of Propaganda’s “Dr Mabuse” were by Bedford, even though I compulsively read every ZTT liner note in the 80s. (He finally got a shout out for the remastered reissue in 2010.)

In 1971 Bedford was commissioned by the BBC to create a piece of music to be conducted by Pierre Boulez at a series of concerts at the Roundhouse. He was told that the event would be themed around audience participation. The result was “ With 100 Kazoos”, a piece for chamber ensemble and 100 members of the general public issued with kazoos.

This kind of attempt to break down the wall between classical music and ordinary people was pretty popular in the early 1970s; perhaps the most famous example was Gavin Bryars’ Portsmouth Sinfonia, an orchestra which allowed anybody to join, regardless of talent, ability or experience. (Brian Eno released their albums on his Obscure label.)

Unfortunately there had been a terrible misunderstanding. Pierre Boulez’s idea of audience participation was people being able to ask polite questions at the end. He refused to conduct “With 100 Kazoos”.

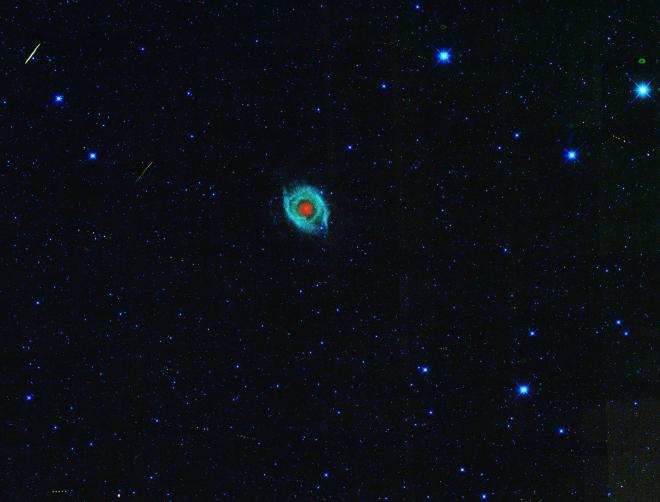

My favorite piece by David Bedford is “Star’s End”, which was one of the first releases by Virgin Records, and features guest appearances by Mike Oldfield and Chris Cutler of Henry Cow. (It was originally going to feature Steve Hillage, and the cover photography was by Monique Froese.) “Star’s End” is a serious yet approachable piece of music; its subject matter is explained by the original intended title, “The Heat Death of the Universe”. (Richard Branson didn’t want the word “Death” in the album title, which is ironic since he originally wanted “Tubular Bells” to have a cover featuring a cracked hard boiled egg with blood running out of it.)

There aren’t too many other pieces of music I can think of that resemble “Star’s End”. It reminds me most of “Mirror Ashes” by John Oswald and The Grateful Dead, which is the second half of an epic two-CD plunderphonic edit made from every performance ever recorded of the Dead’s 1968 track “Dark Star”. The song itself is another interpretation of the theme of dying stars and transitions.

The universe will one day enter a time of eternal darkness. It will be a cold and lonely place. Life will struggle on in islands of complexity, likely separated by impassable expanses of emptiness, but ultimately all living things will die as the stars die and their energy dissipates according to the inexorable laws of thermodynamics. “Star’s End” is an attempt to communicate that reality musically.

“Star’s End” wasn’t released on CD until 1997. When it was, Virgin did their usual so-so mastering job. I discovered today that it had been remastered and rereleased in 2012 on Esoteric Recordings, a subdivision of Cherry Red, one of those intensely annoying record companies that doesn’t seem to like selling high quality digital downloads. So I sighed and muttered and grabbed the CD from the used rack. Only the second time buying this album, I told myself, you’ve bought some albums four or five times…

Yes, the new remastered version is good: an epic dynamic range with no undue compression lets lonely fragments of melody glitter in empty black silence.

Orbital’s 2018 album “Monsters Exist” also takes on the theme of the heat death of the universe. Their track “There Will Come A Time” features Professor Brian Cox telling us it’s untrue that things can only get better, and that in fact ultimately absolutely nothing will survive, that it will all be gone. I’ve no idea whether Orbital are familiar with David Bedford’s work, but I’d like to think that this is his starting to be as influential as he deserves to be.